A few weeks back I wrote an article that rhetorically asked if a lifter should employ the power style of jerk. It was directed mainly at Olympic weightlifters and generally recommended against the power jerk in competition.

Donny Shankle using the split jerk during the 2012 Arnold Classic.

As such, non-competitive trainees who came across the article may have either taken its advice wrongly or rejected it entirely. Those people like to use the power jerk and other overhead lifts in their training for their particular sports. Therefore, it is only fair that I give some advice to those who have more use for the lift in their training, if not in competition.

This week I will to redo the article – but direct it more to the non-competitive trainer. This is especially important since most of the reasons I recommended against the power jerk for Olympic lifters are not as relevant to those not training for that discipline.

My Argument Against the Power Jerk

The main reason I recommended against the power jerk was the fact that it required a higher drive than the split jerk and thereby did not have the same poundage potential when considering efficient competitive lifting. However, this fault becomes a virtue when training those who require strong and quick leg extensions.

“The power jerk is an ideal companion to the power clean, which has often been called ‘the athlete’s exercise.’”

A power jerk will have to be sent several inches higher than a split jerk in order to lock out the barbell. Therefore, it has to be driven harder and faster. This will be of great interest to anyone whose sport requires fast vertical jumping, such as basketball, volleyball, football receivers, shot putters, and many others. For them, a greater drive trumps a deeper split.

Technique in the Power Jerk

In essence, a power jerk is a quarter-squat with the bar in a front squat position, followed by a quick drive out of that squat. This sends the barbell upward while the lifter then performs another quick quarter-squat to allow the arms to receive the barbell at lockout. In a power jerk, the quads are the prime movers, while the hip muscles assist to a great degree. In addition, the abs and lower back have to act isometrically to ensure a proper force transfer to the barbell.

CrossFit athlete Matt Chan demonstrates the power jerk (courtesy of Rogue Fitness).

Anyone doing the power jerk will soon realize it is pretty much a leg and hip exercise. Contrary to appearances, it is not an arm and shoulder exercise. These muscles simply do not get enough work in a power jerk apart from the fact they have to be able to hold the bar at the completion. Even there, that is ideally a bone-on-bone situation, not one requiring pressing strength. It’s all legs.

For those who want to work their shoulders a bit more, the push press is better. You get the leg and hip drive of the jerk at the start and you get some heavy pressing at the finish. These will not help the bottom part of the press, though. You will have to do some overhead presses for that.

Work Out of the Rack

A question often asked is whether the barbell should be cleaned before the jerks are attempted or simply taken from the rack. Due to the extra energy that cleaning the bar requires, most lifters opt for the rack. It makes it a lot easier to concentrate on that lift only.

“Anyone doing the power jerk will soon realize it is pretty much a leg and hip exercise. Contrary to appearances, it is not an arm and shoulder exercise.“

Combining the jerks with cleans will have a beneficial effect on conditioning, but will necessarily compromise the amount of work that can be done on the jerk portion. You only have so much energy – and, remember, we’re talking about trainees who must also do a lot of sport-specific training. They do not want to waste energy in the gym.

Core Strength Is Key

With power jerks there is a need to keep the spinal erectors rigid throughout the drive portion. There is a potential weak spot between the end of the drive and the start of the quarter-squat that finishes the lift. It is at this weak point where lifters will often relax the spine when they are not being careful. That is easy to do in the rush to do the lift.

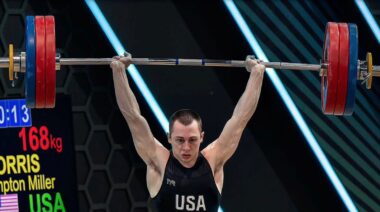

Olympic athlete Kendrick Farris has no problems with core strength in his use of the power jerk.

This relaxing can lead to a hyperextension of the spine and possible compressed vertebrae as the back takes the path of least resistance. Believe me, this is something you want to avoid. Thus, all of the core muscles need to be strong and they need to be held rigid throughout each repetition.

Training Parameters for the Power Jerk

Like most Olympic lifting-derived movements, power jerks are best done with lower reps. One to three are plenty, with threes being most popular. More than that will require a lower weight, which will not have as great a training effect and will also result in a breakdown in technique as the reps climb.

Intensity should be about 80 to 95% of your best power clean. This intensity will ensure that sufficient force is developed in the legs and hips, and that good technique is required. Any less is too light, and any more will not be possible for most trainees. About fifteen jerks can be done at this level of intensity, so five sets of three can commonly be handled. If heavy singles are desired, then only five to seven total should be attempted, with a few lighter warm-up or back-off sets added to increase the volume.

Push Jerks vs. Power Jerks

Sometimes power jerks are referred to as “push jerks.” In actual fact, these are two different movements, albeit with only slight differences:

- In a power jerk, the lifter goes up on his or her toes at the top of the drive and then displaces the feet slightly to the sides as the bar is locked out.

- In a push jerk, such foot movement does not take place. The lifter simply drives upward and receives the bar at the top while making the quarter-squat, all the while being flat-footed.

Because of this foot movement, the power jerk has a higher poundage potential. The rising on the toes adds a bit of extra force to the jerk drive. In addition to that, if the feet are displaced sideways, that enables the lifter to get a slightly deeper quarter-squat, although that extra depth and subsequent advantage is slight. Because of this extra movement of the feet, power jerks will take a little bit more technique and coordination than the simpler pushed jerk.

The Benefit of Power Jerks for Athletes

Power jerks are popular with a lot of athletes, not only for their training effects, but also for the sheer joy of completing such a lift. The bar goes up and quickly snaps to lockout, imparting a feeling of satisfaction as the lifter masters a heavy weight overhead. And best of all, this lift does not require quite as much technique work as the split jerk.

“A power jerk will have to be sent several inches higher than a split jerk in order to lock out the barbell . . . This will be of great interest to anyone whose sport requires fast vertical jumping”

The power jerk is an ideal companion to the power clean, which has often been called “the athlete’s exercise.” Athletes from other sports may not have to become proficient in the competitive version of the clean and jerk, but it is a good idea that they learn to master the simpler power versions of both phases of that lift.

Check out these related articles:

- Would You Be Better Off Power Jerking?

- Push Jerks Enhance Vertical Jumping Performance – Maybe?

- A Jerk Is a Jerk and a Press Is a Press

- What’s New On Pulse Beat Fit Today

Photo courtesy of Becca Borawski Jenkins.