“I’ve got another attempt in me, I know I do.” I hear this all the time, but the question is – do you really? Enter velocity based training (VBT).

VBT can be a key component in taking the guesswork out of your training. It can help you better determine load and perform optimally within a given training session, taking all physiological stressors into account.

Earn the Right to Use Velocity Based Training

I use VBT training for sport athletes and powerlifters. I am slowly implementing it with my intermediate weightlifters, as well. But regardless of sport, the athlete has to earn the right to use this type of training. This means most of my athletes using VBT are trained beginners on the cusp of becoming intermediate to intermediate-advanced athletes.

I don’t recommend this type of training to lifters who are just beginning their strength or sport careers. There is more than enough for you to focus on in your training without concerning yourself with how quickly you are moving the load and what zones you need to be programmed to train within.

When Your Max Is Not Your Max

Tudor Bompa stated that everything leads back to absolute strength. That could not be truer for the powerlifter. For you powerlifters, VBT can be used as a form of auto regulation and can even combined with other auto-regulation philosophies like RPE (rate of perceived exertion). Let’s use an example to get a better understanding of what this approach is and how to apply it.

Billy is a powerlifter and has been training consistently for about a year. He tested his 1RMs two months ago and is basing all his training around those maxes. But here’s the problem: two months ago when he tested those 1RMs, Billy was deep into midterm preparation at school, had just broken up with his girlfriend, and was severely sleep deprived.

“VBT allows you to get the appropriate physiological adaptation for that day’s training session regardless of environmental or personal stressors.”

Now, Billy’s school workload has been reduced, he found a new girlfriend, and he is getting at least six hours of sleep. Do you think that 1RM taken two months ago under those stressful conditions still applies to Billy? There’s a good chance Billy is working from numbers that were not true to his actual strength levels. Thus, he has not been performing as optimally as he could be.

As a powerlifter, VBT allows you to get the appropriate physiological adaptation for that day’s training session regardless of environmental or personal stressors. For powerlifting, we need to generate the maximum amount of force necessary to move the heavy loads required in the squat, bench, and deadlift. To do this we use the measurement of bar speed and work to develop certain physical traits that can improve that force production.

Force-Velocity Zones for Powerlifting

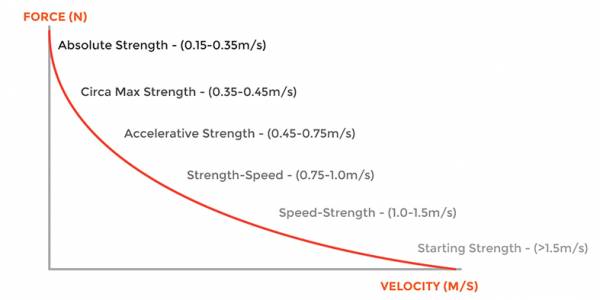

Diagram courtesy of Matt Kuzdub and PUSH.

For powerlifting, I prefer to work within the following zones for the powerlifter along the force-velocity curve:

- Absolute Strength – 0.15-0.35 m/s

- Circa-Max Strength – 0.35-0.45 m/s

- Accelerative Strength – 0.45-0.75 m/s

- Strength-Speed – 0.75-1.0 m/s

As you can see from the diagram, training within those velocity ranges develops the physical traits you desire for powerlifting. These readings are important because we want to develop the specific qualities that lead to performance improvement.

Additionally, by taking and training according to these readings, we can also target different zones for different purposes, like doing hypertrophy work in the accelerative strength zone, strength work in the circa-max/absolute zones, and adding or subtracting loads to account for the velocity change during the working sets.

“I can also use a determined percentage loss, say 10% over the course of a set or sets, that would let me know when it is time to transition you to the next exercise.”

Force and velocity have an inverse relationship due to the fact that as your weight/load goes up (force), the speed at which you lift will slow down (velocity). Therefore, specific trait identification for your sport is necessary through a needs-analysis. What I have outlined is appropriate for powerlifters, but may not be appropriate for you in a different sport.

For any athlete, studies have proven that a loss in velocity can be tied directly to neuromuscular fatigue (NMF). Being able to understand that a decrease in your velocity can be tied to the appropriate time to be done with a particular exercise and move on to the will allow you to perform optimally for that session.

From a coaching standpoint, I can also use a determined percentage loss, say 10% over the course of a set or sets, that would let me know when it is time to transition you to the next exercise or call it a day altogether.

How to Use VBT to Test a 1RM

If you are more comfortable using 1RMs and adjusting every month or two after testing, here’s a good layout for you to use. If you want to see if progress has been made within a mesocycle, 1RM testing could be used before starting the block and then again at the conclusion as a way of measuring the success of your program.

When testing, the closer that number gets to the absolute strength zone (0.15-0.35) the closer you are to actualizing your current strength level and thus a more reliable 1RM. I have seen readings as low as 0.10 during a study conducted in a lab, so some outliers are always present. Your number is highly individual and based on factors like fiber type makeup, age, and the specific demands of powerlifting.

Let’s illustrate this with a 200kg 1RM test example. Billy, from earlier, comes back in and performs a 1RM squat max test with the following readings.

- Squat 1: 1.4 m/s @80kg

- Squat 2: 0.91 m/s @120kg

- Squat 3: 0.67 m/s @160kg

- Squat 4: 0.32 m/s @200kg

At this point, either Billy or his coach will need to make a judgment call. His fourth single in testing came in the range of absolute strength. That’s what we want, but the tricky part is knowing whether or not you have one more attempt in you.

“When testing, the closer that number gets to the absolute strength zone (0.15-0.35) the closer you are to actualizing your current strength level and thus a more reliable 1RM.”

I like to see the technique used, know how much rest the powerlifter had, and then make a judgment call. Depending on those factors, we would either stop the testing here or perform one more single. If it lands in the higher range of absolute strength, there is probably another rep in the tank, but it can be hard to say without knowing the lifter well and how they grind out reps.

VBT During Sets and Repetitions

VBT can also tell the coach or athlete if you are relaxing at a certain point during the lift, particularly after the sticking point, and/or not giving full effort to the reps or set. Ideally, we want to see higher m/s peaks and a consistent average m/s reading across sets. Here is an example from a powerlifting client of mine.

First, you need to know this isn’t a straight set. This was an AMRAP or “plus” set I had him doing at the end of his normal sets of work. As you can see, even after completing numerous sets before this, his average m/s reading during the set was 0.44, right in the range I would like to see as an average for him based on our experience working together and where he was at in his mesocycle. The average m/s reading is exactly what you think it is, an average of the repetition velocities across the set, and this is what powerlifters should focus on during training.

You will also notice his device provided a peak m/s of 0.80, so he is probably giving each rep his all. The peak lets us know whether or not the athlete is truly committing to the whole rep or set or is simply taking his foot of the gas once he is past the difficult point in the lift. If the peak were lower in relation to his average m/s that would be a possible concern, as the loading or technique would need to be looked at.

“VBT can also tell the coach or athlete if you are relaxing at a certain point during the lift, particularly after the sticking point, and/or not giving full effort to the reps or set.”

Let’s bring Billy back one more time for an example of VBT during sets and reps. Billy is programmed to do four sets of eight repetitions in the bench press within the accelerative strength zone. The zone m/s for this is 0.45-0.75. Billy comes in, does his warmup sets, and begins his work sets with 120kg. Bar speed is moving at average m/s of 0.90 for the first set.

This tells Billy he is currently working traits within the strength-speed zone, not what he wants. So he adds 10kg to the bar and does his next set with 130kg, and the velocity reading is 0.70. Perfect. Billy stays with that weight and makes adjustments to stay within the prescribed zone during his remaining sets.

A Starting Point

So now you have a starting point should you want to get into the world of velocity-based training. Just know there is much more research that needs to be done on this type of training and as always, your miles may vary.

Have you used VBT before? Let me know in the comments section below and feel free to ask me any questions you have about this approach to training.

Check out these related articles:

- Introductory Guide to Velocity Based Training

- Is Rate of Perceived Exertion a Useful Strength Training Tool?

- Resistance Training Velocity: Is Faster Better?

- What’s New on Pulse Beat Fit Today

References:

1. Sánchez-Medina L., González-Badillo J., “Velocity loss as an indicator of Neuromuscular fatigue during resistance training.” Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Sep;43(9):1725-34. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213f880. PubMed PMID: 21311352

2. Kuzdub, M., “Introductory Guide To Velocity Based Training.” pulsebeatfit.com, 2015.

3. Mann, B., “Power and Bar Velocity Measuring Devices.” NSCA Hot Topic (2014)

Photos 1 and 4 courtesy of Becca Borawski jenkins.

Figure 2 courtesy of Matt Kuzdub.