In a recent article here on Pulse Beat Fit I reviewed some evidence suggesting the muscles of the core weren’t actually worked best by exercises targeting the core. In the study, exercises like the overhead press had the greatest effect on the muscles of the core. Because these muscles are suitable for stabilization, it seems that they are worked best in a stabilizing role, rather than by being targeted directly.

However, this effect might be different for prime movers. A prime mover is a muscle that actually performs the mechanical work of an exercise. Some of our muscles are less suited for stabilizing and more suited for moving weight around. The results of the study on core muscles makes us wonder what the best way to work a legitimate prime mover is. In a study this month in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning, researchers examined how stability affects the prime movers.

Let’s be clear about the kind of stability we are talking about here. Unstable surface training has long been in vogue, but we Pulse Beat Fit readers know it to be nonsense. To that end, the researchers in this study acknowledged that most real life activities occur on a stable surface, but with unstable implements.

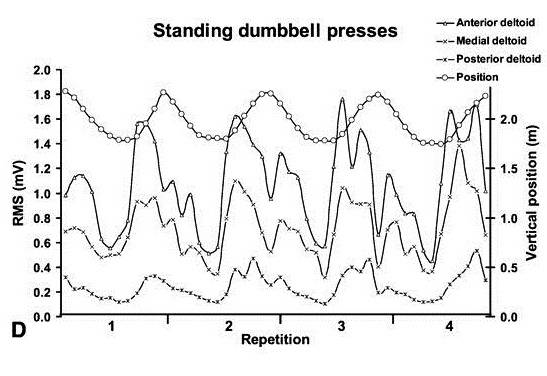

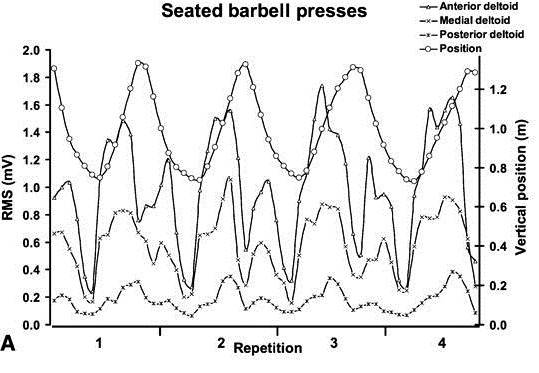

I’ve long believed that more stability is better for muscle. Stability allows you to lift more, and lifting more is better for strength. Strength is good for everything. A simple argument, but there it is. That argument, however, might not always be true. In this study, the researchers looked at the overhead press in the following variations:

- Seated barbell presses

- Seated dumbbell presses

- Standing barbell presses

- Standing dumbbell presses

Their theory was that from sitting to standing and from bar to dumbbell, the stability decreased. As stability decreases, prime movers tend to work harder to move the weight, but the potential load also tends to be lower. It seems like a bit of a balancing act.

In this case, the anterior and medial deltoids, a major prime mover in the overhead press, were worked more as stability decreased. That means they were worked the most when standing with dumbbells. This trend didn’t hold true for the other prime movers that play a lesser role in the overhead press, such as the biceps or the triceps. Using a barbell allows you to “spread the bar” and get more out of engaging the triceps.

In this case, the anterior and medial deltoids, a major prime mover in the overhead press, were worked more as stability decreased. That means they were worked the most when standing with dumbbells. This trend didn’t hold true for the other prime movers that play a lesser role in the overhead press, such as the biceps or the triceps. Using a barbell allows you to “spread the bar” and get more out of engaging the triceps.

There are two things to note that aren’t mentioned in the article. First, I strongly suspect that as you familiarize yourself with a dumbbell lift, the effect on the deltoids will partly diminish. Being in the groove means more stability, but still less weight. Second, the idea that unstable implements increase muscle activity is not a universal rule. Take a squat for example. Dumbbells reduce the weight lifted in a squat to such a degree that it would be impossible to achieve the same muscle activity that you can with a barbell.

There are two things to note that aren’t mentioned in the article. First, I strongly suspect that as you familiarize yourself with a dumbbell lift, the effect on the deltoids will partly diminish. Being in the groove means more stability, but still less weight. Second, the idea that unstable implements increase muscle activity is not a universal rule. Take a squat for example. Dumbbells reduce the weight lifted in a squat to such a degree that it would be impossible to achieve the same muscle activity that you can with a barbell.

So there it is, and it’s mostly food for thought. The dynamics of lifting are such that the stability or lack thereof of the implements you use mind can make or break your results. Test each option, but don’t swallow any dogma whole. Different positions and implements will always have advantages and disadvantages.

References:

1. Atle Saeterbakken, et. al., “Effects of Body Position and Loading Modality on Muscle Activity and Strength in Shoulder Presses,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27 (7), 2013.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.