The debate has raged since 2004. That was the year a CrossFit Journal article hit the internet, touting the benefits of the overhead “American” kettlebell swing over the traditional, eye-level “Russian” swing. Pulse Beat Fit has featured top examinations and arguments from both sides.

While much has been said on this debate, my unique background allows me to speak to both sides. I am an RKC Level II trainer, a CrossFit L1 coach, and former SoCal CrossFit Regionals competitor. I also hold a B.S. in mechanical engineering that informs my analysis of the mechanics, loading, and training effect of each movement.

A Tale of Two Swings

CrossFit supports the overhead swing because of the two reasons that Greg Glassman outlines in his article. First, CrossFit does not advocate partial reps and argues that it seems “neurologically incomplete” to halt the natural range of motion to any movement. The second reason is rooted is basic physics: the higher something is lifted or the more it weighs both equate to doing more work. On the surface, these seem to make sense and prove that the overhead swing offers a greater training effect.

However, the RKC and many other traditional kettlebell communities offer a case against swinging overhead based on three main problems. They hold that the primary argument in favor of the overhead swing is based on a flawed understanding of physics; that the movement is unsafe; and that it reinforces unhealthy positions. Former Master RKC Andrew Read offers a conclusive case for the Russian swing. These rationales often fall on deaf CrossFit ears as the kettlebell community is perceived as elitist and dogmatic.

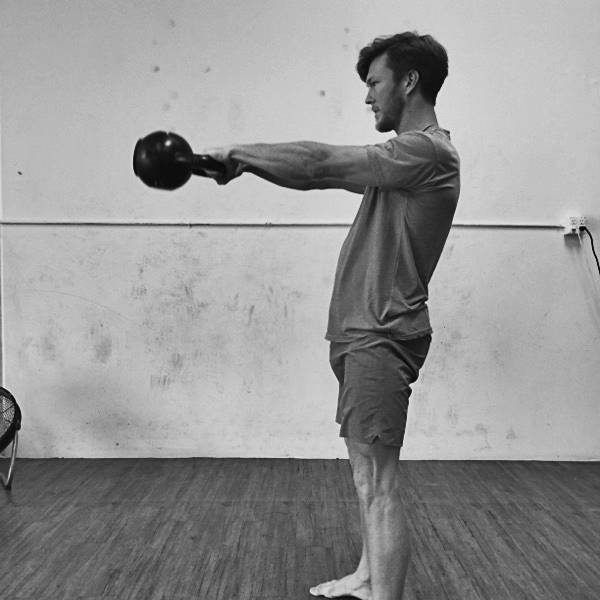

Swing however you want, but understand that the entire point of the kettlebell swing is the generation of force through full hip extension.

Everyone is free to use a kettlebell in any way they choose. If you absolutely love to swing overhead, be my guest, but understand that the evidence against it is crystal-clear: the overhead swing represents unproductive alignment in the top position and offers little to no added benefit in work capacity.

The primary case against the American swing is two-fold:

- The American swing changes the movement pattern and discourages a full hip hinge.

- The overhead lockout position is unsafe and unhealthy for the shoulders.

Let’s take a deeper look.

Deconstructing the CrossFit Argument: Oversimplified Biomechanics

The primary reason that Coach Glassman supports the overhead swing is that it offers greater intensity, the Holy Grail in the CrossFit world. He examines the work required to complete each CrossFit movement with the equation that Work = Force x Distance. An overhead swing moves the same weight twice as far and thus requires twice as much work.

Next, he measures the time to perform each movement to determine the power required to complete both with the equation Power = Work / Time. Power is analogous to intensity and he posits that if an overhead swing (i.e., twice the work) can be done in less than twice the time of a Russian swing, then it offers greater training intensity.

Using these formulae he concludes that the overhead swing offers more intensity, but this reasoning falls apart under greater mechanical scrutiny. More work is required to move the kettlebell overhead because it travels a further distance, but which part of the body performs that work?

Deconstructing the CrossFit Argument: The Upper Body Corrupts the Hip Hinge

The kettlebell swing is meant to train the hip hinge movement. And it does so effectively. Glassman’s assertion that swinging overhead requires the hip hinge to generate twice as much force is an incredibly flawed assumption. Guiding the kettlebell to an overhead position requires action from the arms, shoulders, and upper back. This upper-body involvement could range from minimal (the athlete simply guides the bell into position) to significant (the athlete yanks up and punches through, keeping the bell close to the body).

Most overhead swingers I see favor a strong involvement of their arms to keep the bell moving in a straight line. This is the most efficient line of travel overhead, but it results in heavy involvement from the upper body. Worse, it undermines full hip extension, which is the entire reason for training a swing.

The Russian swing eliminates the variance of power distribution inherent in going overhead.

The upper body involvement actually encourages less generation of power from the hip hinge. The proportions of how the hip hinge and the upper body distribute the work will vary greatly between athletes depending on their chosen style of overhead swing. Determining these proportions would require in-depth biomechanical analysis.

Many athletes performing an overhead swing adopt a bottom position of chest up and knees forward. This loads the front of the body instead of the posterior chain and does not represent a hip hinge. Yet, if the goal is to efficiently put the bell overhead, this bottom position prepares your body to move the bell in a straight line. Therefore, the most efficient way to perform an overhead swing cannot be deemed a swing at all, because it becomes a completely different movement pattern and training effect.

Perhaps we should just call the overhead swing a two-handed snatch and the debate will cease. But even then, the overhead swing still represents a compromised position.

Deconstructing the CrossFit Argument: The Problems With the Overhead Lockout

Here’s a simple test to demonstrate the problem with the overhead position in a kettlebell swing. Lie on your back or stand against the wall. Squeeze your butt and core to stabilize your spine. Slowly raise your arms overhead. Notice the point at which your back lifts away from the wall or floor and your ribs jut out in front. This is the end range of your shoulder mobility. To achieve a true overhead position (i.e., arms flat against the wall or floor) you probably have to bend at the low back. Now repeat the experiment with your arms out in front and hands together. Not even close, right?

In my years of coaching, I have met surprisingly few people with shoulders that allow for a sound overhead position with a barbell. I have never seen a person who can perform an overhead swing without a bend in the low back. I know that it is possible because I’ve seen high-level gymnasts perform a broomstick pass-through with hands nearly touching. However, for the general population, the overhead swing represents an unsafe position for your shoulders. Shoulder injuries are the number one ailment I see in the CrossFit community. The overhead swing isn’t the source of all of them, but it certainly isn’t helping.

Deconstructing the CrossFit Argument: Does Range of Motion Equal Training Effect?

Setting the issue of shoulder safety aside, do athletes truly get an improved training effect by going overhead?

To answer that, let’s start with the examples of form displayed in the 2004 article. The male athlete demonstrating the American swing shows atrocious form in the top position. His knees are bent, his hips shy of full extension, and his low back is hyperextended. This shows the type of body alignment required for overhead lockout with hands together.

In the photo meant to be an example of the Russian technique, he swings the bell far above the proper end range. Glassman asserts that a Russian swing represents half the range of an American swing, despite that fact that his own photos display the athlete improperly swinging the bell to roughly 70% of the height of the overhead swing. This negates his entire mathematical analysis.

Glassman’s primary argument is that the faster cadence of the Russian swing does not make up for the gap in intensity that the shorter range of motion creates. But the photos in the article demonstrate a much higher end position than a proper Russian swing, which throws into question his timing of the movements.

The question Glassman appears to answer (that no one is asking) is whether a full American swing is better than ¾ of an American swing.

Patrick McCarty offers a valuable point that CrossFit is more concerned with overall intensity, rather than training isolated movement archetypes like the hip hinge. Even if there is a loss of intensity, we cannot possibly know how much work comes from the hip hinge or the upper body.

The American swing requires many of your core stabilizing muscles to release to make the compromised overhead position possible. This increases the time between reps and decreases the amount of whole-body engagement per rep. The American swing only requires full engagement at the bottom. This, coupled with the longer range of motion, greatly extends the cycles of tension and release.

By contrast, the Russian swing requires engagement at both the top and bottom with cycles of release only when the bell is in motion. A Russian swing requires visible contraction of the abs, glutes, and lats in the top position to halt the motion of the bell. This creates a systemic isometric contraction that mirrors a standing plank. From the top, the athlete actively pulls the bell back down into the bottom position. This decreases the time between reps, a concept known as impulse in the engineering world. Faster impulse creates a greater training effect because it requires more energy use per unit of time.

Deconstructing the CrossFit Argument: Train in Russian, Compete in American

Do I swing overhead? Yes. I enjoy the odd local CrossFit competition a few times a year, but I approach the overhead swing understanding that it does not represent a sound position. I mindfully maintain my bottom position and have good mobility in my upper back and shoulders. I know that a small amount of imperfect loading in the name of fun and community will not result in an injury. This is a conscious examination of my personal abilities and priorities. At most, I perform 100-200 overhead swings per year.

I do not use the overhead swing in my training and I do not program the overhead swing for my athletes. If I wish to give them a hip hinge and overhead kettlebell movement, I use the tried-and-true kettlebell snatch. Single side overhead lockout allows for much safer alignment. If an athlete’s mobility allows for both arms overhead, we use the double kettlebell snatch.

Despite the CrossFit’s dogged assertions, the American swing offers little to no training benefit over the Russian swing. Proper Russian swings offer high intensity, systemic isometric engagement in the top position, and full action from the hip hinge. These elements combine to offer a much greater training effect, with no risk of poor alignment. When deciding which swing is right for you, choose a movement that focuses on the hip hinge and greater engagement. Avoid training positions that reinforce the postural misalignments we are all combating. Swing Russian!

More on the Great Kettlebell Debate:

- Rationalizing the Swing: Why the American Swing Is Wrong

- 2 Safer Alternatives to the Overhead Swing

- The 10 Commandments of the Kettlebell Swing

- New on Pulse Beat Fit Today

Teaser photo courtesy of Aaron Vyvial.

Photo 1 courtesy of CrossFit Impulse.

Photo 2 courtesy of Justin Lind.

Photo 3 courtesy of CrossFit Stars.