When the Olympics came to London in 2012, not only did it provide the British public with an enthusiasm extravaganza rarely seen in a long and chronically reserved history, it brought one of the most prolific athletes of our time to our backyard: Usain Bolt. The Jamaican sprinter was touted as the most naturally talented runner the world has ever seen, and many newspapers ran stories about his mystical, genetically pre-destined success.

The ability to lift double your bodyweight is not decided at conception. Talent is the product of hard work.

I didn’t like this portrayal of high-level sporting ability. The notion that people are born talented has always made me feel uneasy. It seems exceptionally bleak that a person’s sporting success is determined in the zygote. Not only does the concept deny athletes recognition of their effort to reach their sport’s premier level, it discourages trainees who struggle at the start of their journey. After all, if genetics determine achievement, there’s no reason to persevere if you fail on your first attempt.

My intuition has always told me that society has talent wrong, and that everybody possesses the capacity to forge unlimited skill in any discipline they choose. Imagine my delight when I discovered that the finest neurologists in the world believed this too, and even better, they could prove it.

Myelin and The Talent Code

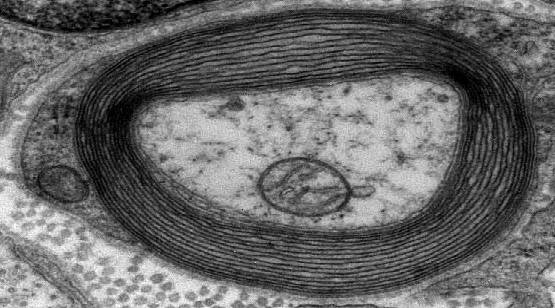

Every human skill from learning how to walk to snatching a barbell is created by chains of nerve fibres in the brain linking together to form a neural circuit. As we practice a skill, electrical impulse signals fire down the wiring and the circuit is brought to life. In The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle presents groundbreaking research on myelin, a neural insulator in the brain that wraps and insulates this circuit, making the signal fire stronger and faster. The more the myelin layers around the circuit, the more precise and proficient the skill becomes.1

See those concentric circles? That’s myelin.

Coyle found that every human is capable of growing more myelin, but it only grows according to certain signals. He went on to devise a “code” for its development: a simple formula to hack skill building and send the idea of God-given talent spinning into the obsolete.

Coyle’s talent code is:

deep practice + ignition + master coaching = talent

These are the signals myelin requires to grow and develop skill mastery. As single entities they are powerful, but combine them together and magical progress occurs. Deep practice facilitates a mindful and self-corrective approach to training that maximises learning from errors and promotes focused application; ignition sparks interest and emotional involvement from the athlete, spurring that practice on; and the catalytic addition of a master coach provides a grand conductor for the whole process.

In this three part series, we’re going to look at your training through the lens of this code. We’re going to show you how to grow more myelin to improve your weightlifting skill.

Three Pitfalls to Deep Practice in Weightlifting

As a weightlifting coach, the most common complaint of any given athlete I train is: I’m not progressing fast enough.

Usually, the issue is not that the athlete isn’t practicing enough, but that they aren’t practicing in the right way: i.e. actively, mindfully, and aware of their errors. Coyle coins this way of practicing as deep practice: the first element of the talent code.

I’ve found there are three common pitfalls to deep practice in weightlifting. Read through each one and be sure you’re not slipping down one of these slopes.

Pitfall #1: You Aren’t Actually Practicing

With the advent of the Internet, there is a wealth of weightlifting footage at an amateur’s fingertips. YouTube start-ups like Hookgrip and All Things Gym put out hundreds of technique videos a year that slow down, speed up, and isolate each stage of the Olympic lifts for analysis and viewing pleasure.

They’re an invaluable resource for showing a beginner how the lifts work. And that’s awesome. But myelination has been proven to be impossible without any practical application. If you only watch a good game instead of actually playing it, your skill development will be limited in return.

The US Air Corps found this in their flight schools in 1934. Guided by the belief that pilots are born, not made, the US military certified a recruit good to fly if he passed several weeks of ground school and didn’t experience in-flight nausea. The system was a disaster, turning out fatalities of fifty-percent at times over the course of several decades. When Edwin Link Jr. devised the first flight simulator and pilots began to actually practice what they had learned, everything changed, and the Air Corps went on to play a significant part in winning World War Two in 1945.2

The moral? Real-time practice wins wars. So by all means geek out on Lydia snatching 124kg – but get down to the gym afterwards and get your myelin factory churning.

Pitfall #2: You Aren’t Concentrating

Olympic weightlifting is one of the hardest athletic skills you can undertake. A beginner not only has to overcome physical barriers of flexibility, mobility, and strength, but they have to learn inordinately complex motor patterns. If you want to become a better runner, you can put on your shoes three times a week, blast some tunes, put one foot in front of the other, and improve exponentially. The same is not true of our sport of weightlifting.

“Knowing about myelin gives us power over our development again and unlocks boundless belief in our capacities. It puts the responsibility back in our hands.”

Concentration is critical in deep weightlifting practice. Pick a day in your week to train the lifts alone and eliminate distractions as much as possible. Write your workout on the whiteboard instead of keeping it on your phone, and turn off your notifications for an hour. Set up a chair for rest periods and use that time to think your lifts over instead of checking your Facebook. Reflect if you missed and recall your coach’s cues to help guide your next one. Visualise your perfect lift in first and third person. Hone your focus to make your practice as deep and productive as possible.

Pitfall #3: You Aren’t Correcting

If I haven’t driven it home enough, in weightlifting you fuck up a lot. It’s normal and means two things:

1) You are trying.

2) You are learning.

With that said, errors are only useful feedback if you remain aware of them and correct them. Luckily, mistakes in our discipline are self-apparent: a significant error usually means a significant crashing of the bar to the floor.

You still need to be proactive and ask a coach to watch your lifts for corrective feedback. If a coach isn’t available, video your lifts and show him or her later. If finances allow, invest in some remote coaching. Many elite weightlifters are offering video analysis with their programming packages these days. It’s not as ideal as in-person coaching, but should at the least provide you with some corrective cues to take your lifting forward with.

Your Potential is Limitless

Our genetic code is the blueprint for every single cell in our body. My intention is not to deny that completely, or the role that anthropometrics may play in weightlifting. My argument, and Coyle’s, is that the role of the human genome in talent has been overstated, and its ability to be moulded and maximised is limitless. Knowing about myelin gives us power over our development again and unlocks boundless belief in our capacities. It puts the responsibility back in our hands. Hopefully, you will begin to feel some more ownership in your training through learning about it.

The first and most powerful element in the talent code is deep practice. Meet me here next time for the second element: ignition.

More Like This:

- Perfect Practice Makes Perfect – Or Does Nature Trump Everything?

- The 4 Stages of Skill Acquisition

- Learning Sucks, But You Should Do It Anyway

- New on Pulse Beat Fit UK

Photo 1 courtesy of Rx’d Photography.

Photo 2 courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

References:

1. Coyle, Daniel. The Talent Code (2009, Arrow Books) p.5

2. Coyle, Daniel. The Talent Code (2009, Arrow Books) p.22