This article was co-authored by Craig Marker and Pavel Tsatsouline.

Want to become a better CrossFit athlete? Knock huge chunks off your Fran time? Athletes who applied these training methods designed by old-school Soviet Olympic coaches made statistically significant improvements versus a control group who continued to train using CrossFit protocols.

By applying these specific training protocols and focusing on anti-glycolytic training methods, we were able to increase strength and strength endurance in trained CrossFit athletes. Athletes in our training group saw faster times for Fran and Karen when compared to the control group, as well as significantly greater improvements in the clean and jerk.

Train to Success, Not Failure

Russian coach Andrey Kozhurkin competes in a uniquely Russian sport called the “winter polyathlon.” It adds pull ups to the traditional biathlon of cross-country skiing and rifle marksmanship. The pull ups must be strict and done within a 4-minute time limit. Kozhurkin has done 60 pull ups in 4 minutes. What do you think his training is like?

If you are imagining “pull or die” marathons to failure and beyond, you are mistaken. Kozhurkin avoids pump and burn like a plague. His approach to training is decidedly anti-glycolytic. The Russian coach made a global observation on the two diametrically opposed philosophies of stimulating adaptation:

- Create the unfavorable conditions of the specific load to stimulate the organism adapting to them.

- Create conditions that enable the organism to avoid (or at least delay) the unfavorable internal conditions of the specific load that lead to failure or prevent continued work at the required intensity.

There’s a better way to train than simply pushing to failure over and over again.

Let us use strength training as an example. The majority of bodybuilders and recreational athletes use the first approach. They train to failure, knocking against their limits over and over and slowly pushing them up. In contrast, strength athletes such as Olympic weightlifters and powerlifters follow the second approach. The first 1,000-pound squatter, Dr. Fred Hatfield, famously proclaimed that one ought to “train to success,” as opposed to failure.5

In endurance training, the first philosophy represents the consensus. Coaches expose athletes to deeper and deeper levels of exertion to improve acid buffering. This is what Arthur Jones from Nautilus called “metabolic conditioning” back in 1975.4 But a number of Soviet scientists, Prof. Yuri Verkhoshansky among them, decided to go against the consensus. They pursued the second strategy, and found ways to minimize glycolysis by expanding the alactic (quick) and aerobic (long-term) energy system windows. “Anti-glycolytic training,” or (AGT) was born.

Verkhoshansky’s work began in the USSR back in the 1980s, and culminated in the twenty-first century. Using his research, the Russian national teams displayed remarkable performance breakthroughs in a mind-numbingly diverse array of sports: judo, cross country skiing, rowing, bicycle racing, full contact karate.

If it worked for all those sports, why should it not work for CrossFit?

At StrongFirst, we have been successful with anti-glycolytic training (AGT) endurance protocols for kettlebell quick lifts (e.g., swings, snatches), pull ups, and push ups. We also have seen a lot of “what the hell” effects, like improvements in non-trained events and body composition. We decided to push the envelope and apply AGT to CrossFit to test whether these protocols will work in a glycolytic environment.

Testing AGT for CrossFit: Methods

We signed up forty CrossFit athletes as subjects. They had at least one year of CrossFit experience, and most had competed at the local level. These athletes did not make the regional level of the CrossFit Open, but most finished in the top 500 of their region. Twenty athletes were assigned to the AGT protocol, and twenty matched subjects served as controls participating in regular CrossFit programming.

The controls continued to train with CrossFit as usual, while the experimental group followed the AGT program described below. The endurance components of this program were designed according to the guidelines by Professor Victor Selouyanov, the leading AGT researcher. The strength and hypertrophy components were designed according to the guidelines from the StrongFirst Lifter manual. The experiment lasted six weeks.

All athletes were tested in two CrossFit benchmark workouts: Fran and Karen. They also performed a 1RM clean and jerk a week before the experiment and right after it. It is worth noting that Fran puts a greater premium on strength than Karen.

Fran:

For time, 21-15-9 reps x 3:

- 95lb thruster

- Pull ups

Karen:

For time:

- 20lb wall ball x 150

Testing AGT for CrossFit: Results

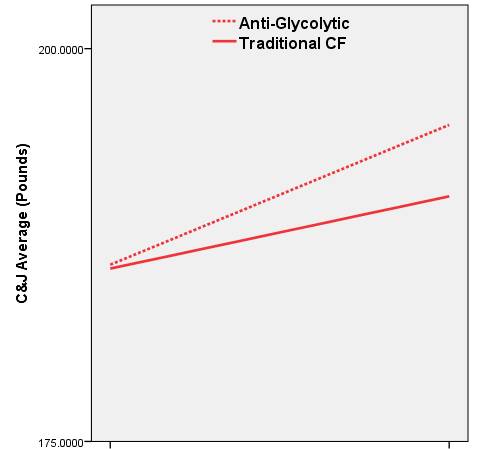

The experimental group made statistically significant improvements in the clean and jerk that were greater than the control group. The anti-glycolytic group added about 9lb on their clean and jerk, while the control group added about 3lb. These results did not seem to differ across gender, so the results are combined.

Average Change in Clean and Jerk

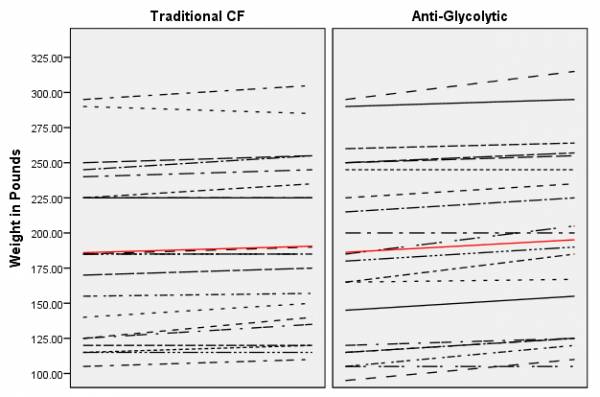

Individual Change Trajectories for Clean and Jerk

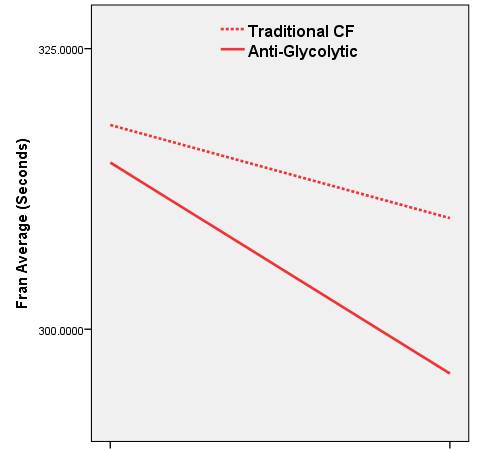

The anti-glycolytic group made statistically significant improvements in Fran. These improvements were greater than the control group: about a 15-second reduction versus a 6-second reduction.

Average Change of Fran Time

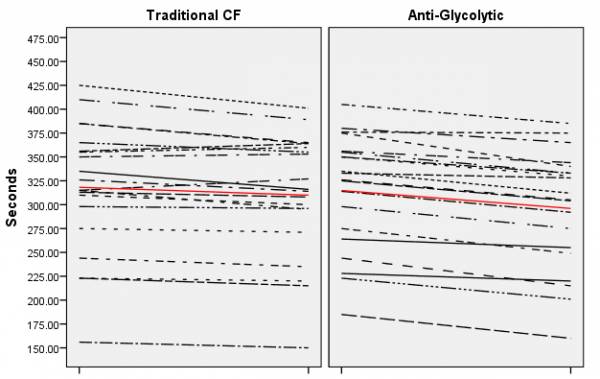

Individual Changes in Fran Time

Both groups experienced similar and significant improvements in Karen. One effect that was not measured, but noted by many of the athletes in the AGT, was a loss in fat and gain in muscle while on this program.

Testing AGT for CrossFit: Summary

Anti-glycolytic programming is helpful for many athletes. In this example, it helped CrossFit athletes achieve stronger Olympic lifting performance and Fran times. The traditional endurance training model for sports focuses on improving acid buffering systems by progressively exposing the organism to greater acidosis. As shown by our experiment, similar results can be achieved with anti-glycolytic training.

The AGT Program for CrossFit

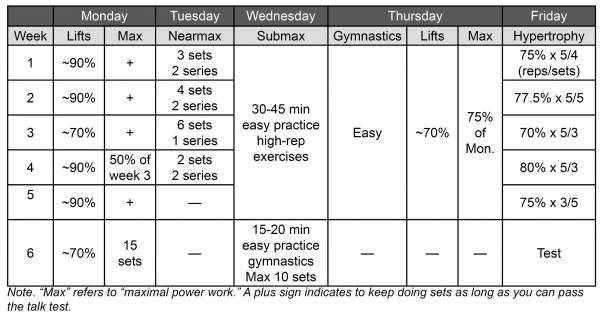

The protocol below outlines the specifics of the six-week AGT cycle we used with our CrossFit athletes.

Note that we compromised by paying equal attention to several training components over a six-week period. This is not an optimal approach to long-term planning, but a necessity for a six-week experiment. If you choose to write training plans based on ours, write a periodized plan with moving targets.

We used the following Russian classification of predominantly anaerobic work of different intensity :

- Maximal power exercises (90-100% intensity contraction, <20sec duration)

- Nearmaximal power exercises (70-90% intensity contraction, 20-50sec duration)

- Submaximal power exercises (50-70% intensity contraction, 1-5min duration)

In the table they are referred to as “max,” “nearmax,” and “submax.” The subjects trained five days a week, Monday through Friday.

Monday: Heavy Lifts and Max Power Endurance

A. Heavy lifts practice

Work up in singles to a heavy weight in 3 lifts of your choice. Typically finish with ~90% 1RM. If you feel exceptionally strong, you may go heavier and even try a PR. If, on the other hand, you feel flat, just do several singles with ~80% 1RM.

On deloading weeks, when 70% intensity is indicated, do 5 or so easy singles with ~70% 1RM.

Use different lifts and variations each week:

- Snatch, jerk from the rack, front squat

- Strict weighted pull up on rings, strict weighted handstand push up, strict weighted pistol

- Kettlebell throw for distance, muscle clean (no knee dip), barbell military press

- Front squat, bench press, deadlift

- Clean grip power snatch, push press from the rack, strict weighted tactical pull up (palms facing forward, thumbless grip, neck or chest must touch the bar)

B. Max power endurance

Max power alactic work with aerobic recovery is the key to the plan’s success. You must be competent in “Russian” kettlebell swings. Select a kettlebell you can perfectly and powerfully swing for 15-20 reps (your choice of one-arm or two-arm swing). Do maximally powerful sets of 5 reps on the minute. Keep going in this manner, as long as you can pass the talk test right before the next set. You must be able to speak in sentences. This is imperative.

Do not cut the rest short to save time or just to make yourself more miserable. Verkhoshansky warned:

“…it is necessary to pay attention to the recommended duration of the rest pauses both between sets as well as between series. Under no circumstances should these recommendations be neglected; time economy leads to a loss in training efficiency.”

Actively rest between sets. Walk around and shake the tension out of your muscles. Stop when either your power drops off or you can no longer pass the talk test (hopefully 20-40 minutes).

In week 4, do 50% of the sets you did in week 3. Do 15 sets in week 6 to taper before the weekend’s test.

This model modifies traditional interval training by decreasing the work periods and increasing the rest periods, all while increasing the power of muscular contractions. As a result, anaerobic glycolysis does not get the opportunity to go full power. The muscles mostly work alactically and recover aerobically.

More suffering does not equal maximum progression. Work-rest cycles that pass the “talk test” may be more beneficial.

Tuesday: Nearmax Power Endurance

This is your competitive outlet. For success of the plan, it is imperative that you select all-out efforts under one minute in duration. Choose exercises you can safely perform at high intensity and change them every week. Some options:

- Russian kettlebell swing (two-arm): 60sec

- Double kettlebell clean and jerk (if you have the skills): 60sec

- Sprint: 200-400m

- Hill sprint: 150-300m

- Rowing sprint: Max strokes/45sec

- Wingate bicycle ergometer x 30sec

Rest for 3-5 minutes between sets with 15-20 minutes between series. A “series” is a group of sets., e.g., if the plan shows 3 sets/2 series, do 3 sets with 3-5 minutes between them, then rest for 15-20min and repeat the drill.

Limiting glycolytic sets to under a minute and significantly increasing the rest periods between them reduces the acidosis to moderate levels. According to Russian experts, high levels of acidity kill mitochondria, while moderate levels promote their growth.

Wednesday: Submax Power Endurance

On Wednesday, practice many exercises typically done for higher reps in CrossFit: pull ups, thrusters, double-unders, etc. Spend 30-45min practicing them in a slow circuit observing the following rules:

- Do not exceed 50% of your max reps.

- Do not exceed mild local fatigue in the end of a set (no “burn”).

- Must pass the talk test before next set.

You can read about the logic behind this type of work in the Long Rests article.

The last Wednesday is organized differently: 15-20min of easy gymnastics practice followed by 10 sets of max power endurance with swings.

Thursday: Mixed Skills

A. Gymnastics: A very easy practice.

B. Light Lifts Practice: Do 5-10 perfect singles with ~70% 1RM in the lifts you will be maxing next week.

C. Max Power Endurance: This is a light day. Do 75% of Monday’s sets., e.g., 15 sets if you did 20 on Monday.

Friday: Hypertrophy

Apply the cycle listed in the table to the following exercises:

- Front squat

- Bench press

- Hammer row

Rest for 5 minutes between sets. Do not superset or tri-set the exercises.

Less Burn, More Gains

Unlike many Soviet training secrets, the details of this program will not take years to reach the training populations of other countries. Avoiding glycolysis in your training will expand the alactic and aerobic windows and limit how much work needs to be done in “the burn.”

When everyone else was prescribing acid baths for “conditioning,” Prof. Verkhoshansky had the courage to go against the tide. Do you have what it takes to try such a radical idea yourself?

More Tips for CrossFit Success

- CrossFitters: Stuck in a Strength Rut? Implement These Strategies

- Defeat Poor CrossFit Movement With These Work-Rest Strategies

- CrossFitters: 5 Steps to Immediately Improve Your Weightlifting

- New on Pulse Beat Fit Today

References

1. Verkhoshansky, YV. Programming and Organization of the Training Process. Moscow: Fizkultura i Sport. 1985. (In Russian)

2. Maximov DV, Selouyanov VN, Tabakov SE. Physical Preparation for Sambo and Judo. Moscow: TVT Division. 2011. (In Russian)

3. Verkhoshansky, YV, Verkhoshanskaya, NY. Special Strength Training: Manual for Coaches. Verkhoshansky.com. 2011.

4. Jones, Arthur. “Flexibility and Metabolic Condition.” From Nautilus and Athletic Journal Articles, Accessed March 2016.

5. Hatfield, Frank. “Intensity.” Strength Advocate, August 16 2015.

Photos courtesy of Jorge Huerta Photography.