Work and recovery go together to give adaptation. Adaptation is the sole reason for working out. Whether you chase bigger arms, a ripped midsection, or a bigger total, the way to get there is through adaptation.

Whatever your goal might be, make sure you have ample recovery to adapt to your workouts.

In today’s ever-rushing world, many neglect the importance of recovery, or even have a sound recovery strategy in place. My last article addressed how this might be best accomplished and provided a way for you to track your training so you could make better progress.

The Cliffs Notes version: It boils down to a basic equation. Training effect = work x recovery. If we take T (training) to be “1” for a typical session, then to make the TE (training effect) actually show the benefits of the training, the R (recovery) needs to be at least equal to 1.

But over the last few weeks, I’ve fielded quite a few emails from people asking about how the information they are tracking can best be used. The standout problem always revolves around one thing – misunderstanding how hard you should be training.

Recovery and Adaptation

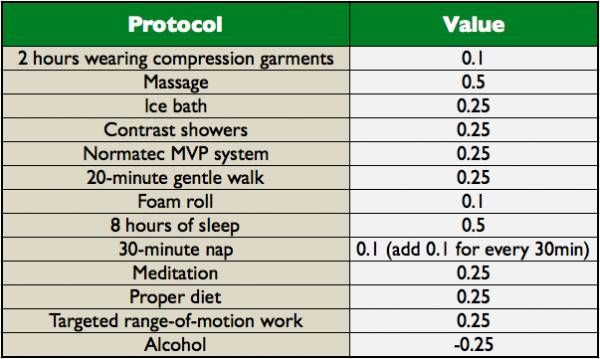

If you’ve got an athlete or client who is really focused, then you’ll see from the chart that he or she will be lucky to score 0.85 for recovery on a daily basis. That equates to eight hours of sleep, a really good diet, and foam rolling daily. I’d go so far as to say this client or athlete is likely a superstar given the attention he or she is paying to what needs to be done to make progress outside the gym.

But if a superstar can only hit 0.85 on a regular basis, then how hard should you be training if you want to see adaptation? For adaptation to take place, you need to ensure ample recovery is there – like credits in the bank. The goal of the equation is to roughly match the amount of work and recovery you do over a period of time. In other words, to ensure you don’t go backward, if your recovery averages 0.85, then your training should average slightly less in order to allow for recovery.

“The standout problem always revolves around one thing – misunderstanding how hard you should be training.”

I’ve written many times about using 70% as the magic number to keep training progressing forward. There are only three variables you can manipulate to allow this to happen – intensity, volume, and density.

To digress slightly, this is where the modern definition of intensity can lead people astray. If your workout is one of those drawn-out affairs using all kinds of high-intensity techniques such as drop sets, then there is no actual way to gauge intensity. The only way you can use intensity as a parameter to adjust is to base it off percentages of your best efforts – otherwise known as your repetition maximums (although it doesn’t necessarily have to be off your 1RM).

How to Adjust Volume

The reason volume is first in the list of things you can moderate is because it is the simplest. You can easily check from one week to the next whether you lifted more reps or not than the previous week. For example, using the standard 5 x 5 as our benchmark at a given weight, your workout goal is to complete 25 reps. If you get those 25 reps and can go up in weight the following workout, then congratulations – you’ve adapted.

“It might be tempting to just do all your sessions at 80%, but modulating intensity actually leads to faster gains.”

So if 25 reps is what allows you to adapt, then accomplishing equals less than 0.85 when viewed as part of the training equation. More likely it is 0.80 or even slightly less. If we take 25 to be 0.80, then 31 reps is 100%, 28 reps is 90%, and 70% is 22.

To keep the volume to a point where we can successfully adapt, we need to average around 0.8 for the week. If we do whatever the exercise is with whatever this particular load is in the following format we’ll get adaptation:

- Workout 1: 28 reps

- Workout 2: 22 reps

- Workout 3: 25 reps

You’ll notice the hardest workout is followed by the easiest to allow recovery. You’ll also notice the sessions are at 90%, 70%, and 80%. It might be tempting to just do all your sessions at 80%, but modulating intensity actually leads to faster gains. The higher volume sessions force adaptation while the lower volume sessions allow for recovery.

Higher volume sessions force adaptation while lower volume sessions allow for recovery.

How to Adjust Intensity

West German sports scientist Dietmar Schmidtbleicher found that big jumps in intensity could lead to faster gains in both size and strength. There are two ways to go about doing this. Either plan your session out so the average intensity for the lift comes in at 0.8 or plan successive sessions so the average over time is 0.8 or lower.

In a session:

- 2 sets at 60%

- 1 set at 70%

- 1 set at 80%

- 1 set at 90%

- 1 set at 95%

- Average intensity – 75.8%

Within a week:

- Workout 1: sets at 90%

- Workout 2: sets at 70%

- Workout 3: sets at 80%

- Average intensity – 80%

Note: This method makes it easy to go slightly overboard. It assumes volume is equal between workouts. You’ll find, using 25 reps as your guideline again, that a workout at 90% may blow you to pieces and force you to take off many days or go excessively light in the following training sessions.

How to Adjust Density

Density is sort of backward compared to the other two variables. Where intensity and volume are about lifting more in the same timeframe, adjusting density is often about lifting less in the same timeframe.

“I’ve written many times about using 70% as the magic number to keep training progressing forward. There are only three variables you can manipulate to allow this to happen – intensity, volume, and density.”

Using our 25 reps as the baseline, you might find that a good workout takes 25 minutes, basically a set every five minutes. So, here’s how a week using density as the moderator would look:

- Workout 1: 27 minutes (90%)

- Workout 2: 36 minutes (70%)

- Workout 3: 31 minutes (80%)

- Average density – 80%

Adjusting density is often about lifting less in the same timeframe.

Your Training Should Match Your Recovery

If you want to keep progressing, then make sure you have ample recovery credit to adapt to your workouts. Using the chart above, you can see how easy it is to get bogged down with one hard workout after another, never allowing yourself the chance to improve. Stay on that plateau too long and you’ll suffer injury or burnout – which is nature’s way of moderating your intensity, volume, and density. (This is a joke, by the way – do not wait until you get injured to schedule back-off sessions.)

There are ways to pump up what you can recover from over time, which I’ll share in the next article. In the meantime, have a look at your training and identify ways to help adaptation by moderating one of the above variables so that your training matches your recovery.

More Like This:

- How Your Recovery Relates Directly to Your Performance

- You Don’t Need More Training, You Need More Recovery

- 7 Essential Elements of Rest and Recovery

- New on Pulse Beat Fit Today

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.