A few weeks ago a friend of mine messaged me. She’d been having some intermittent shoulder pain that was starting to bother her during workouts. The pain was primarily on the anterior aspect of the shoulder and was particularly bad whenever she did push ups or shoulder presses.

Push ups put a lot of stress on the shoulders.

This is a pretty common issue and usually requires a straightforward fix, but before I could even tap out the beginning of a response, she wrote to me: “I think it’s my rotator cuff.”

Sigh.

It’s not really her fault. I see a lot of articles and discussions involving what people believe to be rotator cuff problems. It’s become something of a stock response to shoulder injury or pain: “It’s probably your rotator cuff.”

The truth is quite the opposite. With a few exceptions, most shoulder injuries are not the cuff’s fault. It is just a victim. In this article, I’m going to discuss why this is the case, what’s actually going on, and what you can do to keep your shoulders healthy and happy.

Mechanism of Injury – The Man Holding the Knife

One of the biggest issues in physical therapy is the over-focus on the nature of the injury, while ignoring the mechanism of the injury. Both of these things are important, but for slightly different reasons.

“With a few exceptions, most shoulder injuries are not the cuff’s fault. It is just a victim.”

Early on, the nature of the injury is the most significant factor in determining a proper course of rehab. Muscular, bone, and soft-tissue injuries all require a slightly different approach. Once the physical damage has been repaired, though, understanding the mechanism of injury is pivotal in preventing it from happening again.

When you’re talking about cuff injuries, in most cases the problem didn’t originate with the cuff itself, but much of late-stage rehab will involve rotator cuff strengthening. If you’re a thrower, a tennis player, or involved in any other sport that puts a great deal of strain directly on the cuff, then that approach makes some sense. If your shoulder injury was the result of working out and lifting weights, this approach pretty much disregards the true mechanism of injury.

If the muscles around your scapulae are weak, no amount of rotator cuff strengthening is going to be able to pick up their slack.

Think about it like this. Let’s say you were out walking around and someone stabbed you with a knife. Your immediate concern would be to stop the bleeding. But once that’s taken care of, you still need to deal with the man holding the knife. Why did he stab you?

Was it an accident and he didn’t mean to do it at all? This scenario is analogous to contact injuries and other accidental issues. If the mechanism of injury was truly accidental, it’s probably not worth worrying about too much.

On the other hand, if his actions were the direct result of your own behavior, it’s a more pressing concern. Sure, you stopped the bleeding, but what if he just stabs you again? Staunching the flow of blood is still the immediate concern, but if you never address the man holding the knife, then your problem is never going to be solved.

Scapular Stability – The Common Culprit

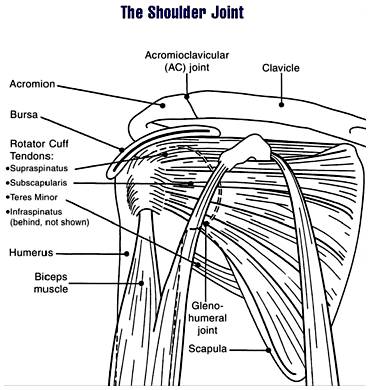

The shoulder “joint” is probably the most complicated joint in the human body because it’s actually a combination of three different joints (or four, depending on who you ask).

- The primary bony articulation of your shoulder is actually on your sternum at your sternoclavicular joint.

- From there, your scapula is attached to your clavicle at your acromioclavicular joint.

- Your scapulae rest on top of the posterior aspect of your rib cage, which provides the surface they move around on. Some people refer to this as the scapulothoracic joint.

- Finally, we have the glenohumeral joint, where the head of the humerus attaches to the glenoid fossa of the scapulae.

Whew, did you get all that? The take-home point here is that the rotator cuff, due to its location, is only capable of stabilising motion at the glenohumeral joint, the third point of articulation.

The muscles around the scapulae are responsible for providing true shoulder stability.

The rotator cuff muscles are found on your shoulder blade. When you see them on a cadaver, they’re tiny, even in specimens with well-developed muscles. By comparison, the muscles around your scapulae (trapezius, rhomboids, and even the latissimus dorsi has a scapular attachment on some people) are enormous. It’s those muscles that are responsible for providing true shoulder stability.

If the muscles around your scapulae are weak and your scapulae are immobile, no amount of rotator cuff strengthening is going to be able to pick up their slack. On top of that, many people who have weak scapular muscles also have poor scapular positioning, which complicates the issue further.

Why Are We So Focused on the Rotator Cuff?

I’m not entirely sure why we’re so concerned with the cuff, to be honest. I think some of it is that rotator cuff repairs are one of the most common shoulder surgeries, which leads people to believe the rotator cuff is a problem. Rotator cuff strength is also easy to measure objectively through manual muscle tests.

“The ultimate goal is to learn what a neutral position feels like and how to consciously activate your scapular musculature so that, with enough practice, the stabilisation becomes reflexive.”

Scapular positioning and stabilisation, on the other hand, is more of an art than a precise science. The human body is incredibly adaptable, which means that even if your scapular positioning sucks, your body can probably find a way to work around it. If you don’t specifically look at the scapular motion and only focus on the movement of the humerus, it may well appear that nothing is wrong.

How Can You Help Yourself?

First and foremost, if you genuinely believe you have a rotator cuff problem, then you need to see a medical professional. Once you’ve been cleared of an actual structural injury, then there a couple of simple strategies you can employ to get your scapulae back on track.

Diaphragmatic and 90/90 breathing exercises are some of the best ways to reset your body’s position to neutral. You don’t necessarily need to live in this new position, but you need to develop the kinesthetic awareness of what neutral feels like.

90/90 breathing demonstration

Once you’ve established a neutral position, you can start with something simple like scapular retraction drills and then progress to prone alphabet raises (T,Y,I) and wall drills like the wall Y.

Prone Y raise demonstration

The ultimate goal is to learn what a neutral position feels like and how to consciously activate your scapular musculature so that, with enough practice, the stabilisation becomes reflexive. Addressing initial pain and dysfunction is usually quick (one to four weeks), but developing reflex stabilisation can take quite a bit longer.

Find the Real Culprit

In my experience, the presentation of an injury is usually the least useful factor in determining a long-term course of rehabilitation. Often the presentation is just the straw that broke the camel’s back. The real issue is the man holding the knife.

Labrum tears, impingement, anterior pain, and rotator cuff issues are all potentially preventable through improved scapular mobility and stabilisation. Accidents happen and some injuries aren’t avoidable. That said, do yourself a favor. Stop blaming your rotator cuff. It’s just another victim and it probably needs your help.

More Like This:

- Avoid Shoulder Injury By Strengthening the Rotator Cuff

- The Facts on Rotator Cuff Injuries and Treatment

- How to Self-Diagnose Your Shoulder Pain

- New on Pulse Beat Fit UK Today

Photos 1 and 2 courtesy of CrossFit Impulse.

Photo 3 by National Institute Of Arthritis And Musculoskeletal And Skin Diseases (NIAMS), via Wikimedia Commons.