Strength training is rarely on the radar for those participating in distance running (or any endurance sport, for that matter), but perhaps it’s time for a change. Science has proven time and again that strength training has a positive effect on endurance performance, and, whether you’re an experienced athlete or a newbie, it just may be the ticket to clocking your best time yet.

Stronger bones, connective tissue, and muscles will help you withstand the rigors of endurance training.

The Evidence

In classic studies performed by R.C. Hickson and colleagues, a group of moderately trained runners and cyclists participated in a combination of endurance and strength training for ten weeks. Researchers observed a 13% improvement in treadmill running and an 11% improvement in ergometer biking; both performed to exhaustion at maximal work rates. They also noted a 20% increase in cycling to exhaustion working at 80% of VO2max.

“The final and most obvious tissue that benefits from strength training and reduces risk of injury is muscle itself.”

A more recent study, published in Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise, investigated the effects of maximal strength training on a group of well-trained distance runners for eight weeks who were simultaneously completing their regular endurance training. Researchers found that the strength training group showed significant improvements in one repetition max testing (33.2%), rate of force development (26%), running economy (5%), and maximal aerobic speed (21.3%) compared to no changes in the control group.

These are just a couple examples of the many studies showing notable improvements in distance running performance after the completion of a strength-training program. The majority of the studies I’ve come across have yielded impressive findings.

How Exactly Does Strength Training Improve Performance?

Heavy strength training is known to increase stiffness in the musculotendinous unit. In fact, The Journal of Physiology published a study that reported an 18% increase in tendon stiffness in subjects who performed an eight-week resistance-training program. The increased stiffness results in a heightened ability to store elastic energy during eccentric actions, thereby increasing concentric muscle force.

Another study, published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, found increased muscle stiffness resulted in increased running economy. Researchers believed this to be due to the fact that stiffer muscles and tendons transfer energy more efficiently, reducing levels of muscle activation and energy expenditure.

“The Journal of Physiology published a study that reported an 18% increase in tendon stiffness in subjects who performed an eight-week resistance-training program.”

Another possible explanation for performance improvements is that strength training seems to create an anaerobic reserve of sorts. A study published in the American Journal of Physiology reported twelve weeks of strength training completed concurrently with endurance training resulted in greater muscle phosphocreatine and glycogen content, and lower lactate concentrations at the end of a thirty-minute cycle compared to endurance training alone.

Another study published by the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports found that strength-training cyclists displayed reduced heart rate and blood lactate concentrations during the final hour of a 185-minute cycling test, as well as improved average power production during a sprint in the final five minutes, compared to cyclists who relied solely on endurance training. While these studies were performed on cyclists, who’s to say runners couldn’t experience the same improvements?

Strength training has been shown to reduce heart rate and blood lactate concentrations in cyclists.

Stay in the Game

If setting a new personal record isn’t enough to get you into the weight room, consider that strength training can also reduce your risk of injury. All the wear and tear you put on your body increases your potential of getting sidelined at some point in your career. Regular strength training has been shown to increase bone mineral density, lessening your chance of stress fracture.

Tendons, ligaments, and fascia have also displayed a positive response to resistance training. The Journal of Anatomy published a study that found chronic loading leads to both increased collagen turnover and some degree of net collagen synthesis. Another study, performed on mice, suggested increased collagen fibril diameter, a greater number of covalent cross-links, and an increased number and density of collagen fibrils may contribute to increases in size and strength in tendons.

The final and most obvious tissue that benefits from strength training and reduces risk of injury is muscle itself. Strengthening the muscles that surround your working joints will improve the integrity of the juncture, minimize any unnecessary stress on the supporting tissues, and reduce imbalances. The combination of stronger bones, connective tissue, and muscles, results in a more durable body better suited to withstand the rigors of endurance training.

What’s Stopping You?

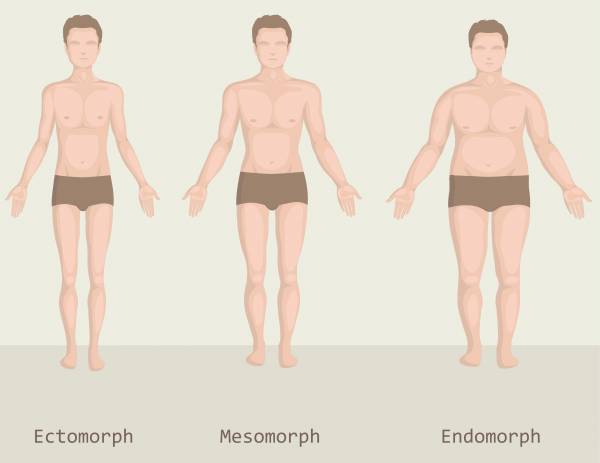

If you’ve avoided weights like the plague for fear of morphing into The Hulk, your worries have been for naught. Runners typically have an ectomorph body type, and individuals with this type of build naturally lack the tendency to gain muscle. This is not to say you won’t build muscle – the idea is that you want to – but you’ll have a more difficult time than someone with a different body type.

“A study published in the American Journal of Physiology reported twelve weeks of strength training completed concurrently with endurance training resulted in greater muscle phosphocreatine and glycogen content, and lower lactate concentrations at the end of a thirty-minute cycle compared to endurance training alone.”

In fact, many endurance athletes lack an important trait necessary to gain copious amounts of muscle – a suitable environment. Unlike plants, it takes more than a little sunshine and water to get muscles to grow. Muscle growth requires a tremendous amount of work in the gym and dedication in the kitchen. Generally speaking, you would need to eat an additional 250 to 500 calories per day in order to gain weight. While this bump in caloric intake is totally doable, chances are recovery from your endurance training is already putting the majority of what you eat to good use, leaving insufficient nutrition for excessive muscle growth to occur.

To be honest, increase in muscle size simply does not seem to be an issue for endurance athletes who add strength training to their existing routine. Although several of the studies discussed above did record measurable increases in strength, none reported significant increases in the cross sectional area of the trained muscles. So you’re likely to get stronger, without getting “bulkier.”

Runners typically have an ectomorph body type, so chances are you’re not going to turn into the Hulk.

Training Considerations

If you decide to take the plunge and boost your endurance training with a few weekly strength-training sessions, make sure you’re smart about it. Wasting time and energy on unnecessary exercises and programming will only hurt rather than help. Choose exercises that transfer directly to running.

Since your legs do most of the work, lower-body work will be the primary focus. Lunges, side lunges, squat variations (front, back, overhead), and toe-heel raises would be appropriate. Consider expanding your program during the off-season for more total-body strengthening, but while you’re in-season, it’s wise to keep things simple.

“One possibility is to schedule your strength training on the two days a week you perform your lower-intensity endurance training. For example, lift weights in the morning and then complete a low-intensity run in the afternoon or evening.”

Perform your strength workout two times per week concurrently with your endurance training, giving yourself at least two days of recovery between strength sessions. Choose two to three exercises per session – for example, forward lunge, front squat, and heel raises. Perform three to five sets of each exercise using a 3 to 10RM, and you’re done. Your strength workouts should be short and sweet, leaving ample time for endurance training.

The lower rep scheme suggested above, means you’ll be working with some relatively heavy weights. While some improvement can be achieved with lighter weights and higher reps, heavier lifts will yield superior results. A recent study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research reported greater levels of change in running economy, countermovement jump height, velocity at VO2max, and 3km time trial performance in subjects who completed a twelve-week strength-training program using more than 70% 1RM compared to those who trained with less than 40% 1RM.

One of the most difficult issues to work out will be how to incorporate resistance training into your existing endurance program without overtraining. One possibility is to schedule your strength training on the two days a week you perform your lower-intensity endurance training. For example, lift weights in the morning and then complete a low-intensity run in the afternoon or evening.

Play around with your programming until you find what works right for you. Ideally, you want the best of both worlds while still getting sufficient recovery.

Since your legs do most of the work, lower-body work will be the primary focus.

The Take-Home

The results are in – with the majority of the research showing that endurance athletes can indeed boost performance with the implementing of a strength program. You know what the science has to say. Now the ball is in your court.

If you’re totally content with your current training and are strictly endurance for life, then keep at it. But if you’re not completely satisfied with your performance and just can’t put your finger on what’s missing, it may be time to pick up a weight.

Try it for a few months, and if you find you’re not feeling stronger and turning in better times, then go back to your old ways. But I bet if you give strength training a chance, you just might surprise yourself.

More Like This:

- Why Runners Need Strength Training (And How to Get Started)

- The 5 Best Plyometric Exercises for Runners

- Weight Training Basics for Runners

- New on Pulse Beat Fit Today

References:

1. Hickson RC. “Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance.” European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology 45:255-263, 1980.

2. Hickson RC, Dvorak BA, Gorostiaga EM, Kurowski TT, and Foster C. “Potential for strength and endurance training to amplify endurance performance.” Journal of Applied Physiology (1985) 65:2285-9220, 1988.

3. Aagaard P, Andersen JL, Bennekou M, Larsson B, Olesen JL, Crameri R, Magnusson SP, and Kjaer M. “Effects of resistance training on endurance capacity and muscle fiber composition in young top-level cyclists.” Scandanavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 21:298-307, 2011.

4. Kubo, K., H Kanehisa, and T. Fukunaga. “Effects of resistance and stretching training programs on the viscoelastic properties of human tendon structures in vivo.” The Journal of Physiology 538:219-226, 2002.

5. Dumke CL, Pfaffenroth CM, McBride JM, McCauley GO. “Relationship Between Muscle Strength, Power and Stiffness and Running Economy in Trained Male Runners.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 5:249-261, 2010.

6. Goreham C, Green HJ, Ball-Burnett M, and Ranney D. “High-resistance training and muscle metabolism during prolonged exercise.” American Journal of Physiology 276: 489-496, 1999.

7. Rønnestad BR, Hansen EA, and Raastad T. “Strength training improves 5-min all-out performance following 185 min of cycling.” Scandanavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 21:250-259, 2011.

8. Kjaar M, Magnusson P, Krogsgaard M, Boysen Møller J, Olesen J, Heinemeier K, Hansen M, Haraldsson B, Koskinen S, Esmarck B, and Langberg H. “Extracellular matrix adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to exercise.” The Journal of Anatomy 208(4): 445–450, 2006.

9. Minchna H, and G. Hantmann. “Adaptation of tendon collagen to exercise.” International Orthopaedics 13(3):161-5, 1989.

10. Støren O, Helgerud J, Støa EM, and Hoff J. “Maximal strength training improves running economy in distance runners. “ Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40:1087-1092, 2008.

11. Hoff J, Helgerud J, and Wisløff U. “Maximal strength training improves work economy in trained female cross-country skiers.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 31:870-877, 1999.

12. Sedona S, Marin PJ, Cuadrado G, and Redondo JC. “Concurrent training in elite male runners: The influence of strength versus muscular endurance training on performance outcomes.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 27:2433-2443, 2013.

13. Bazler CD, Abbott HA, Bellon CR, Taber CB, Stone MH. “Strength Training for Endurance Athletes: Theory to Practice.” Strength and Conditioning Journal 37 (2): 1-12, 2015.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock.