Programming is neither mystical, nor is it mechanical. Nothing within the world of strength training sits on either end of that spectrum. Programming, training, coaching, movement – these are all a mixture of art and science. It’s important to get these two the right way around. Understand the science, then layer the art on top of it. Learn about the principles of programming before filling in the gaps with fancy schemes and protocols.

I know what you’re thinking: it’s all well and good to know the principles, but how does that knowledge impact my day-to-day choices, like what exercises to do, at what percentages?

That’s where this article comes in. Attempting to determine percentages without having an underlying reason for choosing them is like making an awful job of cooking your steak and then adding a nice sauce – largely pointless. You need to know how to grill your steak and cook your veg before you figure out what garnish you’re going to use.

So let’s get started on the cookery lesson.

Any coach worth his or her salt will be happy to explain how your programming relates to your goals. [Photo courtesy of Cara Kobernik]

Figure Out Your Reasons

It’s important to figure out your reasons for strength training in the first place. Programming is about developing and maximizing the required qualities for the task at hand, in a timely manner for that task. That task doesn’t have to be a competition. As an everyday athlete, being strong for life, sport, lifting, and everything in between is just as purposeful and poignant as any other goal. If that is your goal, then that is the task your programming is centered on.

Your first port of call is to perform a needs analysis for your task. Quite literally, analyze what you need in order to do well at your chosen endeavor. Let’s say you’re using CrossFit or a similar modality to train for general strength, health, and fitness. You’ve realized that when your squat, press, and deadlift increase, your weightlifting improves. And when your weightlifting improves, your workout times improve. And when your workout times improve, your fitness improves.

The specifics don’t really matter here. This is an example of a needs analysis – figuring out what improves what until you get to the exercises at the core of your program. You know that a bigger squat, press, and deadlift will cascade up the chain to make you stronger and fitter. And because you’re plugging it back into everyday sport and strength, we’re going to assume you want not just to shift heavy iron, but to lift heavier, get faster, and everything in between, with an emphasis on carryover.

Enter the force-velocity curve.

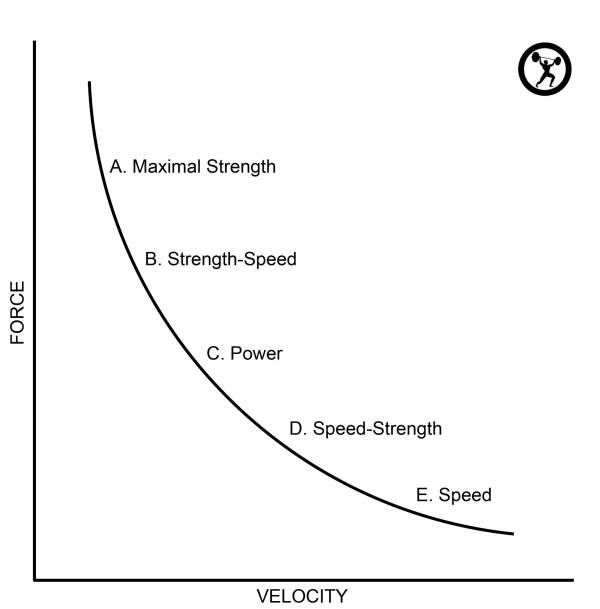

The faster your muscles contract, the lower the force your muscles can produce. [Chart courtesy of Pulse Beat Fit]

The Force-Velocity Curve

This curve shows how the amount of concentric force your muscles can produce depends on the velocity of the muscle contraction. Look at the difference between point A and point E. Point A (maximal strength) is where you’ll bust out a max squat, press, or deadlift. It’s heavy, so to get it moving you need to apply large amounts of force. But the velocity is not going to be high. That thing is going to be a grind. At point A, you can produce a ton of force, but not fast.

Now look at point E (speed). For example, a broad jump, a clapping push up, or a medicine ball slam. This kind of movement is lightweight and fast, but you can’t produce much force here. This isn’t hearsay. The faster your muscles contract, the lower the force your muscles can produce. This is why you can’t lift a heavy weight as fast as you can lift a light weight. Try doing a clapping push up while wearing a weighted vest, and you’ll see what I mean.

In between, you have points B (strength-speed), C (power), and D (speed-strength). These are important. We determined your task is all-round strength and fitness for life, sport, and whatever other activities you fancy doing at any given moment. I don’t know of any sport where you’re not required to be powerful and generate force fast. This means working all the way up and down the force-velocity curve.

Even if you’re only interested in lifting heavy, it’s still important to train aspects of strength other than maximal strength, but that’s a story for another day. The main question we are addressing today is how to program for these all-round strength and speed gains. Let’s look at what happens when we train these qualities with separate focus over a period of time.

What Happens When the Curve Shifts

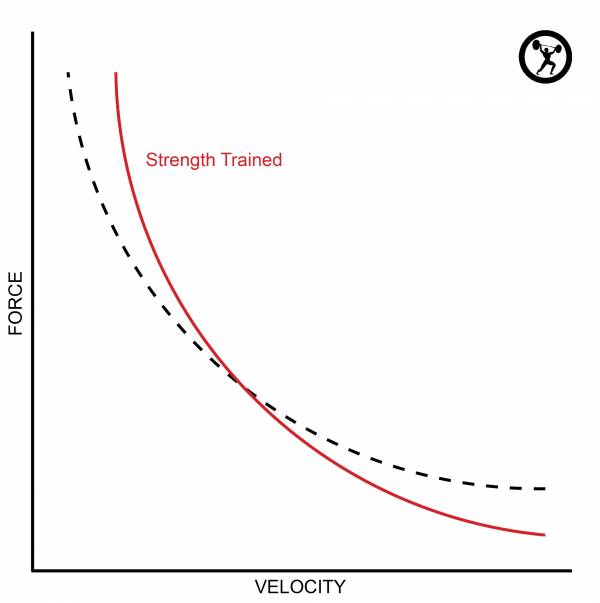

Ever noticed how your legs feel heavy and sluggish when you do a squat program that focuses on lifting heavier and heavier, with no speed work in it? That is because as you train for strength like this, your strength will increase, while your speed will decrease, as you’re not doing any work for it. The shift in your force-velocity curve looks like this:

When your focus is heavy lifting, your strength will increase, while speed will decrease. [Chart courtesy of Pulse Beat Fit]

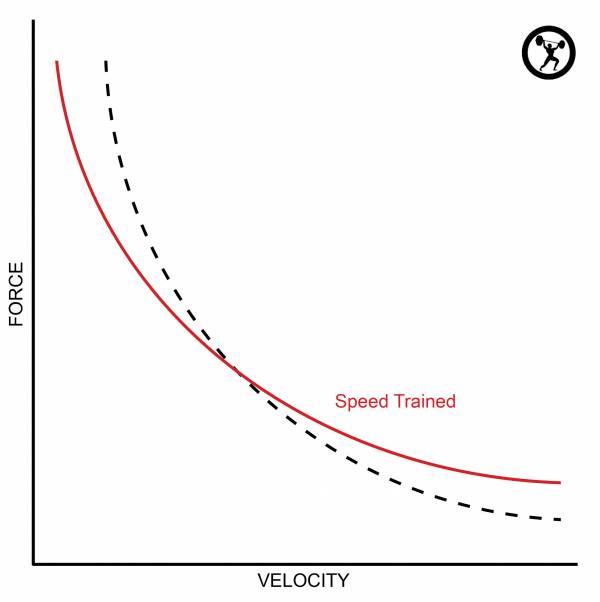

Or maybe you’ve discovered you don’t feel stronger after just doing a whole bunch of conditioning workouts and not much else. That’s because as you train on the lighter weight, higher velocity end of the spectrum, your strength will decrease. The shift in your force-velocity curve looks like this:

When you train on the lighter weight, higher velocity end, your strength will decrease. [Chart courtesy of Pulse Beat Fit]

This is how many people program. It’s block-based programming (typically referred to as periodized programming) with a focus on one section of the force-velocity curve per training block, or training season, over the course of 8-12 weeks. Typically, you’d start with strength, and then progress down the curve to the speed work. The idea is to build strength, then maintain it while you get quicker. If you’re wondering why it’s this way around, have you ever noticed your strength gains take a while to obtain but also a while to go away? Whereas your speed gains are easy come, easy go? That’s why.

This style of programming is useful when peaking for a competition or event, but less useful if you want to be ready to roll all year round. If you’re relatively new to training, it’s even better for you to build a broad base of physical ability now. You can save this more segmented training for later in your training life when you need to specialize more.

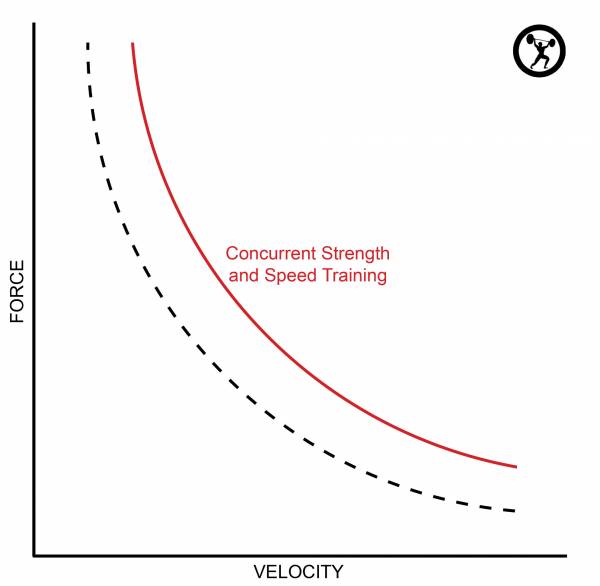

If you’re just training to be all round fast and strong, it’s absolutely fine to train all these qualities simultaneously. Don’t let anyone tell you that you have to follow a “periodized plan” and separate out strength and speed training. That’s not how real life works. That’s not how sport works. Oh, and you can let them know that “peridoized programming” just means having a strategy for your programming. I’m pretty sure that’s what we’re putting together here.

In fact, for you as an everyday athlete, it’s advantageous to train a bunch of points on the force-velocity curve at the same time. At any given point, you won’t be strong at the expense of your speed, or faster at the expense of your strength. This means looking to program strength and speed work for various different movements or body parts in a short cycle, like a day or a week, rather than programming in blocks of months at a time. By programming strength and speed work simultaneously, or as close to it as possible, you’ll push your whole curve to the right, like this:

Training a bunch of points on the force-velocity curve at the same time pushes the whole curve out. [Chart courtesy of Pulse Beat Fit]

Ideas for Programming

Here are two ways you could program for this concurrent strength-speed development:

1. Program multiple types of strength and speed work in a single day.

For an example of this, see my article on The One-Session, One-Exercise, One-Set Strength Plan:

- Warm up

- Perform 2 reps at 80-90% of 1RM.

- Quickly strip the bar to 60%.

- Perform 3 explosive reps at 60%.

- Perform slow (3-1-3) tempo reps to failure at 60%.

- Quickly strip the bar to 30%.

- Perform 3 explosive reps at 30%.

- Perform slow (3-1-3) tempo reps to failure at 30%.

- Perform a static hold at your sticking point at 30%.

Here we are working strength-speed, power, and speed-strength (along with some eccentric and isometric work – we’ll cover these in an upcoming article). You could simply repeat this protocol on different days of the week for different movements. On another day, you could add in some maximal strength work (90%+) mixed with plyometric work, such as:

- Heavy squats and squat jumps

- Heavy deadlifts and broad jumps

2. Program for different points on the curve on different days of the week.

For example, a two-week rotation of:

Week A

- Upper body strength based work (80-100%)

- Lower body power based work (50-80%)

- Upper body speed based work (30-60%)

Week B

- Lower body strength based work (80-100%)

- Upper body power based work (50-80%)

- Lower body speed based work (30-60%)

Build Your Programming

Figuring out how to program sets and reps is not the point of this article. I’ve added the templates above so you have a practical grounding for our points of discussion. What I want you to see here is how when you take your purpose (in this case, general strength, power, and speed), and layer the most fundamental principles of strength training on top of it (in this case, the force-velocity curve and how to train across the spectrum), your programming options become clear.

More on Grounded Programming:

Remember what I said about programming? Programming is about developing and maximizing the required qualities for the task at hand, in a timely manner for that task. If your task is being in a good-to-go state at any given time, your training needs to address the whole strength-power-speed gamut. If you’ve been concentrating on one end of the curve for a while (typically, this will be too much heavy lifting – I’m yet to meet anyone who overdoses on speed work), then spend additional time bringing up the other end so you get that entire shift to the right we observed above.

There’s no need to be paralyzed by training options. Just make sure you are hitting all aspects of the force-velocity curve on a regular basis. If you are weak in one area, add in more exercises or more days for that area. You’ll find yourself fitter, faster, more powerful, and less beat up. And you’ll see surprising effects on your high-end strength, too.

Learn From the Ground Up

It’s easy to get waylaid by the choice of programming options. I can easily write articles giving you strength programs to follow or use. My aim is to help you understand the tenets of strength programming so you can program for yourself and understand programming you are given or see on the Internet.

If you want to be strong and fast for life, ready for anything at any time, don’t be tempted to follow plans that are better suited to competitive athletes. If you’re following programming from a coach or gym and you’re not sure how it fits with these ideas, then show your coach this article and ask. Any coach worth his or her salt will be happy to explain how your programming relates to your goals.

Too many people are dazzled by the supposed mystique of strength programming. And sure, it’s not an exact science. But it’s more than learnable if you approach it from the ground up. Remember – grill the meat first, whether it’s your steak or your purpose. Then add some veg – the fundamentals of programming. The rest is just sizzle.

Get in touch if this article was useful, and I’ll look at making this into a series of pieces to demystify strength programming for the everyday athlete based on the force-velocity curve.