So many people are in pain – way too many. Stretches and mobilizations prescribed to reduce it may work for some and not for others, which only contributes to the frustration and confusion. For this reason, it is extremely useful to have some familiarity with current pain science.

I don’t offer a treatment program or a diagnosis, but I offer something of arguably equal value: the knowledge to objectively decide the best course of action for you. If you have been grappling with pain – chronic or acute, localized or widespread – read on to learn the true nature of that which ails you.

Learning About the “Enemy”

Pain is so intrinsic to the human condition that we often don’t stop to consider its characteristics. The simplest explanation is that pain is when something hurts. Something is bothering you, motivating you to stop what you are doing, change your position, or otherwise avoid what you believe to be causing the discomfort.

Most people associate pain with bodily injury. Although there is often a correlation, there are more complex cases such as chronic pain and phantom pain where no physical damage is evident. In fact, pain is largely a neurological phenomenon. It is a sensation modulated by the brain, based on inputs that are not only sensory but also social, emotional, and psychological. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines it as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”1

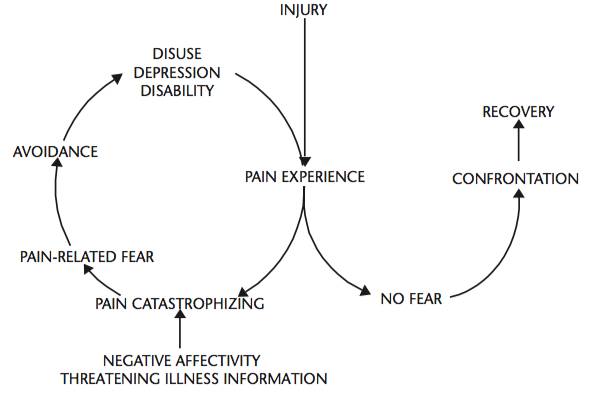

“Most people are used to physiological explanations for their ailments, so they don’t realize that with pain there can be a vicious cycle at work.”

Notice that emotions are mentioned in the definition. Being plagued by pain is stressful and disheartening. But most people are used to physiological explanations for their ailments, so they don’t realize that with pain there can be a vicious cycle at work. Persistent pain exacerbates stress, which in turn can lock the body even deeper into the pain pattern. There is much research documenting this link between the tangible and the intangible when it comes to pain.2,3

How Does It Work?

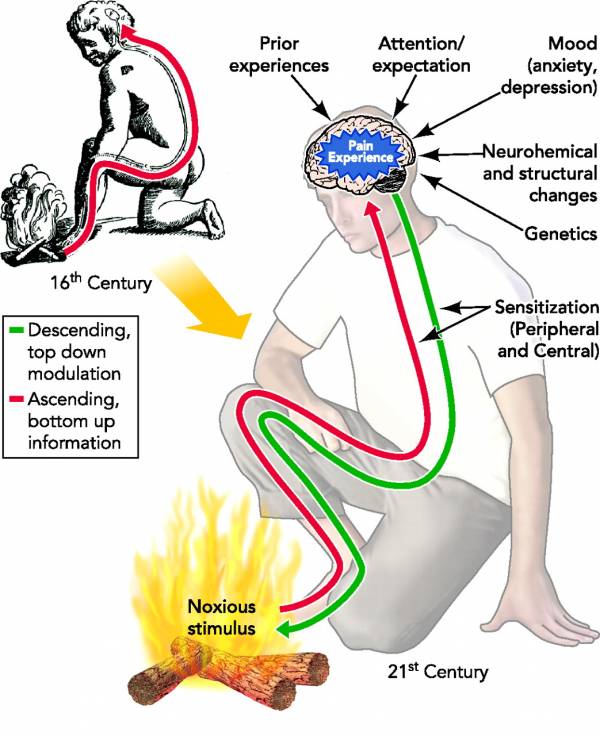

Older models of pain put forth that an injured site shoots pain signals to the brain – in other words, that pain originates at the tissue level. But we now know this is not entirely accurate. There are certain cells called nociceptors that detect noxious stimuli and relay this information to the brain. But from there, it’s up to the head honcho to create the sensation of pain. It does not actually come from the local site.

The relationship between brain and body

By no means am I saying that pain is caused by the mind, or that it’s all made up in your head. Rather, think of the brain as a factory foreman who uses past experience, machinery inspections, worker reports, and other markers to regulate operations. Nociception is important in producing pain, but so are other, less tangible things. Subconscious factors are among the resources your brain weighs when determining how much pain to create. In this process, your brain also looks to past experiences, social context, beliefs, and a wide variety of other variables.

In light of this, researchers such as Ronald Melzack, Patrick Wall, Lorimer Moseley, and David Butler developed and furthered something called the neuromatrix model of pain.4 It takes note of the nuances discussed above, and so the recommendations for treatment are more holistic. Foremost among the interventions is education about the science. After all, beliefs that are limiting or misleading can contribute to chronic pain. The first step in alleviating unnecessary burden is to learn about and understand it.5

The cycle of pain and outcome

My Back Is Bad, My Pain Is Bad – or Are They?

One common idea is that biomechanics, posture, tissue quality, and other structural issues are root causes of pain. This is an incomplete and even harmful idea if it convinces people that, for example, their body proportions are “horrible” or they have permanent scar tissue. These are self-defeating ideas that further develop fear and avoidance – not a place from which you can tackle your pain.

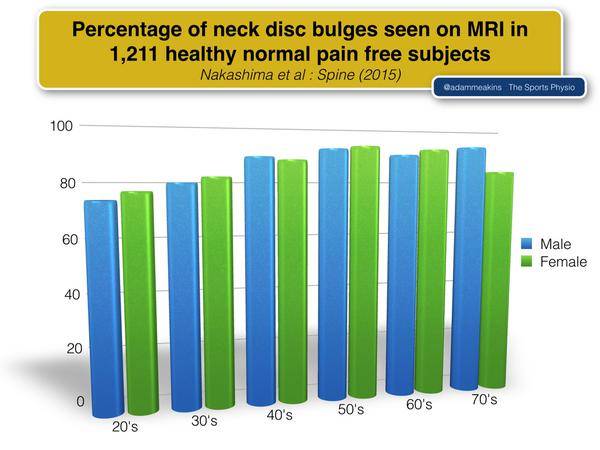

If body structure were absolutely key in producing pain, how could you explain the majority of study subjects with “bone and soft tissue abnormalities” in their knees or those with “abnormal findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans” who feel no pain? 6,7

No one likes pain, obviously. But it is necessary to survive. It is a strong incentive to avoid actions and behaviors that might harm you. Some people are born without sensitivity to pain, a condition called congenital analgesia.8 While you may think them lucky, they are at far greater risk for deadly injury because they do not realize when they have hurt themselves.

The bottom line is that pain is an alarm system, an output of the brain meant to defend against perceived threats by encouraging you to avoid them. These perceived threats usually involve tissue damage – a bruise or a broken bone. In these cases, addressing the physical problem will alleviate the “threat” and therefore the pain. But when keeping your body healthy and active is not enough, it’s time to do more sleuthing to determine and confront the source of your pain.

When you’re ready to make a change, start off small. Give your body the pampering it deserves so it can muster its recovery resources and feed a positive stimulus, rather than a negative one. Mindfulness is one tool you can use. It relieves stress, which can positively impact how you feel physically, plus it empowers your mind to remain calm, focused, and in control.

“The bottom line is that pain is an alarm system, an output of the brain meant to defend against perceived threats by encouraging you to avoid them.”

If certain positions or movements cause discomfort, find ways you can regress – use less range of motion or move more slowly – so there is no pain. Explore movements that are agreeable. This teaches your nervous system that not everything is dangerous. As more positions become pain-free, you will find you are less scared and are building momentum to liberate yourself from pain.

Perhaps the most important course of action, though, is reasserting your own worth and goals. Pain is a nuisance, but don’t let it get the better of you.

Being a Student

All of this fascinates me because I, like any other athlete, suffer pain. Sometimes it can be difficult to tell why it happens or whether your active lifestyle and workouts contribute to it in some way. I am not a researcher, and I do not make a living by treating other people’s pain. I am just seeking to be informed and to be an active participant in my own experience with pain.

I have found quite a few pioneering resources to be helpful:

- Pain Science is run by a former massage therapist who takes great care to scour the research and critically examine conventional wisdom.

- Better Movement targets not only the topic of pain but also the nervous system in general, movement skills, and how these all relate to physical performance.

- Lorimer Moseley updates along with his team over at Body in Mind, presenting new perspectives and recommendations based on the latest research for pain patients.

- SomaSimple is a forum of not only physical and manual therapists, but also all others who are committed to intellectual rigor, thorough review, and mature discussion.

If traditional methods of treatment don’t seem to work for you, there is still hope. You can take responsibility for learning the latest pain science and applying it to your own story. You can investigate your lifestyle, emotions, and relationships to your body and pain. You can choose to be mindful and take control of your own struggles.

Just remember: if it hurts, it means your brain cares about you.

More on pain and recovery:

- Understanding the Brain is the Key to Being Pain Free

- Facing the Pain: Let It Be Your Guide

- 5 Steps to Safely Train Around Lower Back Pain

- New On Pulse Beat Fit Today

References:

1. “IASP Taxonomy.” International Association for the Study of Pain. Accessed June 13, 2015.

2. Nils Georg Niederstrasser, P. Maxwell Slepian, Tsipora Mankovsky-Arnold, Christian Larivière, Johan W. Vlaeyen, and Michael J.L. Sullivan, “An experimental approach to examining psychological contributions to multisite musculoskeletal pain,” The Journal of Pain 15 (2014): 1156-65.

3. Tim V. Salomons, Tom Johnstone, Misha-Miroslav Backonja, Alexander J. Shackman, and Richard J. Davidson, “Individual Differences in the Effects of Perceived Controllability on Pain Perception: Critical Role of the Prefrontal Cortex,” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 19 (2007): 993-1003.

4. Ronald Melzack, “Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain,” Journal of Dental Education 65 (2001): 1378-82.

5. Adriaan Louw, Ina Diener, David S. Butler, and Emilio J. Puentedura, “The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain,” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 92 (2011): 2041-56.

6. K.A. Beattie, P. Boulos, M. Pui, J. O’Neill, D. Inglis, C.E. Webber, and J.D. Adachi, “Abnormalities identified in the knees of asymptomatic volunteers using peripheral magnetic resonance imaging,” Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 13 (2005): 181-6.

7. Maureen C. Jensen, Michael N. Brant-Zawadzki, Nancy Obuchowski, Michael T. Modic, Dennis Malkasian, and Jeffrey S. Ross, “Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain,” The New England Journal of Medicine 331 (1994): 69-73.

8. “Congenital Insensitivity to Pain.” Genetics Home Reference. March 30, 2015. Accessed April 6, 2015.

9. Hiroaki Nakashima, Yasutsugu Yukawa, Kota Suda, Masatsune Yamagata, Takayoshi Ueta, and Fumihiko Kato, “Abnormal Findings on Magnetic Resonance Images of the Cervical Spines in 1211 Asymptomatic Subjects,” Spine 40 (2015): 392-8.

10. Ulrike Bingel and Irene Tracey, “Imaging CNS Modulation of Pain in Humans,” Physiology 23 (2008): 371-380.

11. Steven J. Linton and William S. Shaw, “Impact of Psychological Factors in the Experience of Pain,” Physical Therapy 91 (2011): 700-11.

Photo 1 courtesy of Shutterstock.

Photo 2 courtesy of The American Physiological Society.

Photo 3 courtesy of The American Physical Therapy Association.

Photo 4 courtesy of Adam Meakins.